By Yvonne Tran

Yvonne and her mom Christine circa 1990

There is one part my mother’s routine that she has kept over the years. Before she enters the kitchen to begin her culinary creations, she always turns on the portable stereo to station 106.3 FM, Saigon Radio. It wouldn’t matter that I was in the middle of my favorite Lizzie McGuire episode, or that my dad was about to vacuum the entire house. She would turn it on even when all these other noises drowned out the announcer’s voice.

Sometimes my mom would perk up from peeling carrots and sing along to a Khánh Ly song. On other occasions, she would laugh hysterically at the oblivious woman whose husband was obviously cheating on her. “This is like Jerry Springer!” she would comment. I was used to having cups of milk forced into my hand by my mother because the bác sĩ on the radio said I would surely die if I didn’t drink enough of it.

The Vietnamese-language radio station became the soundtrack to my childhood, and I hated it. It drove me insane that in the age of sleek iPods, my mom still had bulky, stereo cassette players littered in every corner of the house to play her beloved station. Saigon Radio was this old-school, crackling medium with more advertisements for medicinal herbs and plastic surgery than actual programming. I would never comprehend the lightning-fast language the announcers conversed in, nor did I enjoy the constant wailing of Cải Lương, Vietnamese folk opera. To westernized ears like mine, it sounded like parrots attempting to sing. What were they singing about that was so sad? Why didn’t the song have a melody? When does it end? These questions would torture me, so I always got up to change the station to what I thought were more sophisticated, American tunes.

15 years later, I am driving my mom home, and I turn on the radio in my car. Coincidentally, I left my pre-settings on Saigon Radio, so the station blares out of the speakers. At this point in my adult life, I had already gone through the period of soul-searching in college where I came to accept my identity and wanted to relearn the language I had lost. I would listen to Saigon Radio to mimic the speech patterns of the announcers. Every so often, I actually danced along to the cha cha cha music that played and found the crazy callers entertaining.

Although I didn’t understand every single word of it, I finally appreciated the journey and culture that the station represented. Fleeing Vietnam as a refugee of war was an experience that left an indelible hole in my mom that could be temporarily filled by the comforting sound of her mother tongue. The radio was also a surefire way to drown out the memories of abuse she suffered at home and humiliation she faced as an immigrant in America. She was able to laugh, meditate, and learn new things about the world when she listened. Perhaps even the white noise reassured her that she wasn’t alone in the world. She told me once that when she was younger, her parents were very strict and even prohibited music, so she secretly bought a radio and hid it under her covers. It was one of the most precious things she had ever owned because it was hers.

My mom stared at the speakers, baffled.

“I didn’t know you listened to this station. I thought you didn’t like it.”

“I’m trying to practice my Vietnamese, Mom.”

I turn the volume up so that we could both listen together.

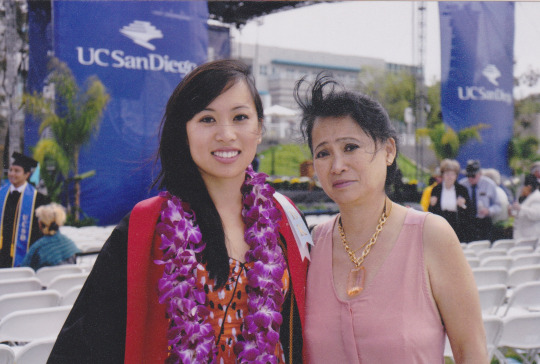

Yvonne and her mom Christine at the University of California, San Diego graduation in 2011.

About the Author: Yvonne is an Orange County native who is always on the lookout for good stories to tell through multimedia and opportunities to highlight issues she cares about. She received her Bachelor’s in Communication from UC San Diego and Master’s in Communication Research at Boston University. She is currently on the Board of Directors at the Vietnamese American Arts and Letters Association (VAALA).